Assumptions

Networking

Networking is critical in the modern world, as we use it all the time to connect to Instagram and send emails. (You probably already knew this…)

This chapter is for giving a quick run down of networking and what is involved in moving data around. There’s a lot, lot more than I’ll go through here, but I’ll try to give you what you’ll need to do the absolute basics in the blue teaming.

What You’ll Learn

- The OSI Model

- The different layers of network communications

- IP Addresses

- TCP and UDP

- Network Ports

The OSI Model

(By MichelBakni - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=66641106)

This is the OSI model, its used to divide the networking process in layers. The OSI has 7 layers, but we really care about the bottom 4 (Transport, Network, Data Link, Physical). Having layers allow different protocols to manage different parts of the communication process and be interchangable. (For example, at layer 1, we could use optical (fiber) or copper cables. At layer 2, we could use the protocols for wireless (802.11) or Ethernet. This is all without changing any other layer). The OSI model helps to encourage the abstraction of components to simply changing things around without messing everything else up.

Each layer has its own encapsulation or packaging. The data starts at the top and is packed in more and more layer information until it is sent. The layer information is used to move the data to its destination, where it is unpacked from all the layer information.

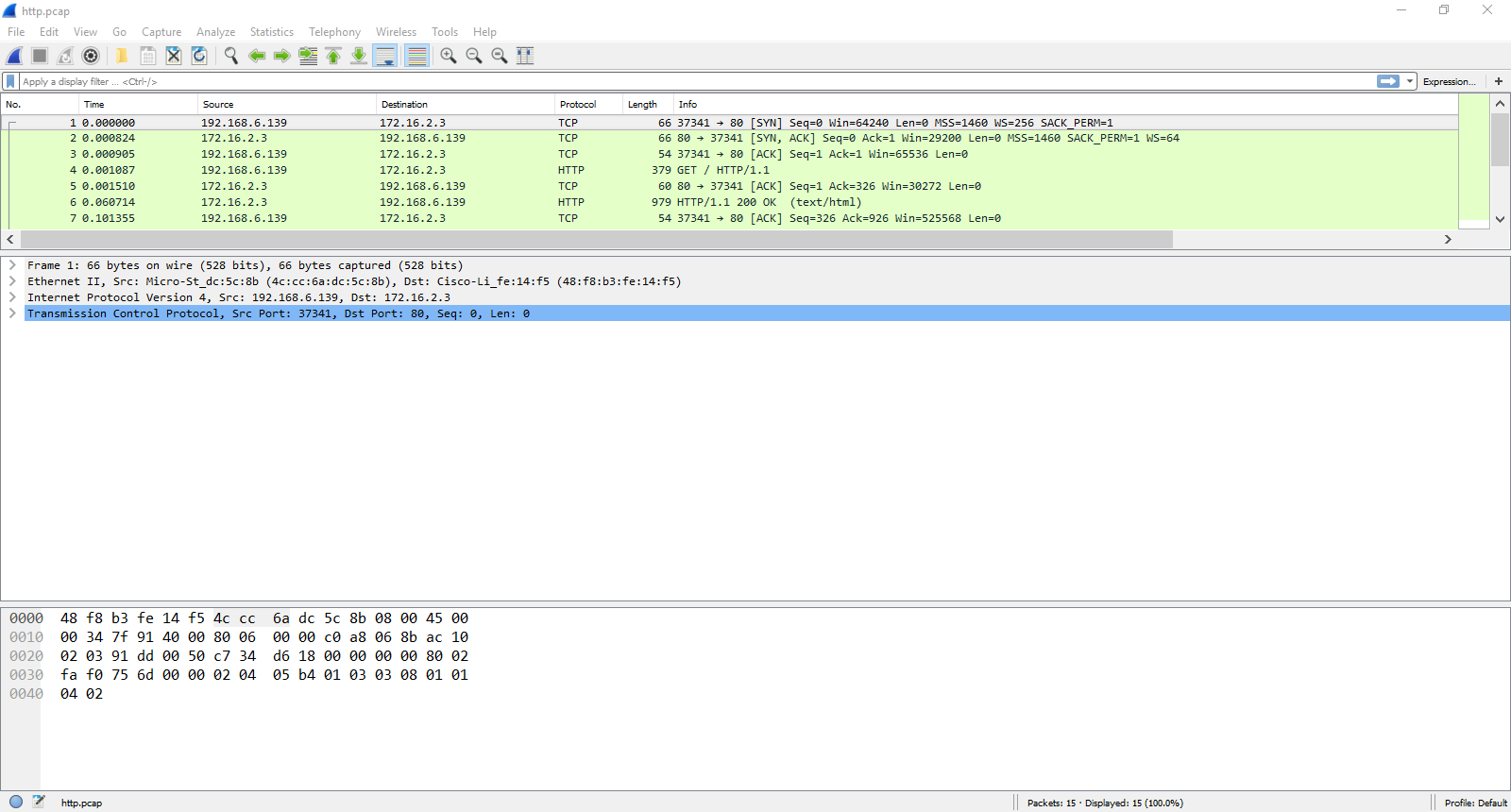

Seeing Network Communications

A tool commonly used to view network traffic as it enters and leaves a system is Wireshark. It’s usually referred to as a packet sniffer. It has a commandline-based cousin called tcpdump.  . Packet sniffers are usefully for see everything that’s coming in or out.

. Packet sniffers are usefully for see everything that’s coming in or out.

Wireshark gives us a nice interface, and displays the packet chopped up into layers. We’ll use this to visualize network traffic to learn about the layers. If you want, you can download Wireshark, install it, and download this pcap (it stores packet capture data). You should be able to double-click the pcap once Wireshark is installed to open it.

The top is a list of packets. Click one to view details about it. The details and the layer sections appear in the middle. Click the arrows on the left to get more details on each section. The bottom of the screen is the raw bytes.

Physical Layer

This is the stuff we actually send on. This is usually a cable or wireless signals that carry the data from point A to point B. In virtualization, this is virtual as well.

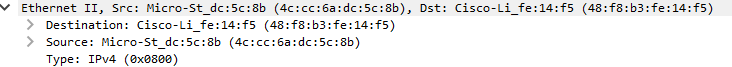

Data Link Layer

The most common protocol you’ll find here is Ethernet. In Wireshark, this is the second section from the top section. It should say Ethernet II. The main thing we’ll focus on here is the two addresses marked by Destination and Source. These are MAC addresses. They are used to identify computers at layer 2. Layer 2 only cares about local communications between computers on the same network (for this, we’ll be defining this as a collection of connected devices). It’s kinda like apartment numbers. It’s only relevent to a particular group.

MAC addresses are assigned on the Ethernet hardware, so you don’t usually have to worry about giving a computer a MAC address. (You can, however, change the MAC address or make new MAC addresses for virtual network interfaces) A switch device will use a MAC address to move frames (what the packaging at this layer is called) from once device to another.

The Type field is used to indicate what’s in the next layer up, in the Network layer.

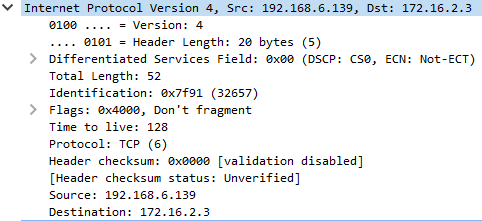

Network Layer

The next section down in Wireshark is layer 3, the Network layer. The protocol that is almost exclusively used here is the Internet Protocol (IP)… protocol. There’s two versions, IPv4, which uses addresses like 192.168.122.1, and IPv6, which uses addresses like FE80:0000:0000:0000:0202:B3FF:FE1E:8329 (Try memorizing that!) IPv4 is the most common (and easiest to remember). IPv6 was/is supposed to replace IPv4, as it has many many many more addresses you can use, but IPv4 is still the most common. You’ll meet up with IPv4 most often, but don’t ignore IPv6! It’s still usable, and many commands have IPv6 versions.  The source and destination addresses are in the

The source and destination addresses are in the Destination and Source fields.

Layer 3 only cares about end-to-end communications, kinda like a street address. Similar to sending a letter around the world (or next door) with a street address, IP addresses can be used to send across the world (or the network next door).

This address is the one you’ll be setting a lot and be messing around with the most. So we have a dedicated section to them.

IPv4 Addresses

IP addresses are divided into octets (this is because there 8 binary digits per section): <octect>.<octect>.<octect>.<octect>. The biggest number that can go in the octet is 255 (the biggest number 8 binary digits can represent).

When using an IP addresses on a computer or network device, its always paired with what’s called a subnet mask. This subnet mask is not sent with the data, but used by devices as a sort of guide. Subnet masks are used by devices to determine what’s in their local network and what’s not. They usually look something like this: 255.255.255.0 (similar to an IP address) or in “slash notation” /24. (This number is the total number of bits in the subnet mask, remember each section has 8, so 8 + 8 + 8 = 24) The number of bits in a subnet mask can be increased and decreased to make the local network bigger or smaller in a process called subnetting. We won’t get into subnetting here, it’s a bit complicated. (If your interested, there’s plenty of resources online)

There are two special addresses in a local network. The first address numerically (the .0 when using /24) is reserved to represent the entire network as the “network address”. Don’t assign it to a device. The second address is the “broadcast address.” This is the last address (.255) and it is used to send to everybody on the local network. Also do not assign this address to a device.

There’s also another special address, 255.255.255.255. This is the broadcast address of everything and any network. If this is the destination address, then its basically addressed to everybody! Don’t assign this address to any device.

Transport Layer

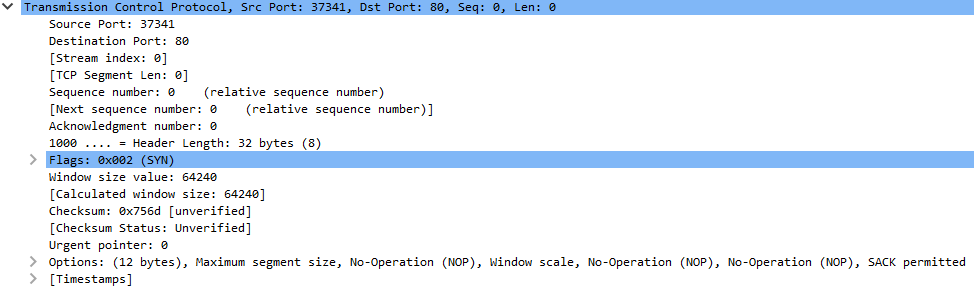

The next layer is the Transport Layer. It doesn’t have addresses, but is used to identify what service the data is destined for. This layer also manages how the whole data arrives. There are two main protocols for this layer, TCP and UDP. Our example uses TCP.

TCP

TCP ensures two sides are talking and the data arrives intact and in the right order. It uses the “three-way-handshake” (the first three lines in Wireshark is this handshake) to negotiate the connection.

(By N-21 - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7972116)

TCP has flags to indicate the state of the connection. A sender sends a packet with a SYN flag, and gets a packet with the flags SYN and ACK (acknowledgment) set. A packet with ACK is sent in response to complete the handshark. TCP uses sequence numbers to keep things in order, with packets sent with ACK flag set to acknowledge data up to a certain point has been received. When its done, TCP uses another handshake (the last four lines in Wireshark) with FIN (finished) and ACK flags to tell each side they are done.

UDP

The other protocol, UDP is much easier. It doesn’t care if a connection is made and essentially just sends the data without bothering to check if it gets there.

Ports

Ports are used by both TCP and UDP to determine what service data is destined for. (e.g. is the data for a web server? a mail server?) Services will reserve “listening” on a port, waiting for data destined for that port. Both ends will have a port. Services, like web servers, listen on “well-known” ports that have been assigned to that type of servive. For example, web servers listen on port 80 (You can see this in the Wireshark above as the Destination Port). The port of the sender is usually randomized from ports of a larger port number (maybe something between 32768 or 61000, the Wireshark image above has port 37341) and identifies the sending program in the response.

On most systems, using ports below 1024 requires admin privileges

Basically, any program can listen on a port, so it’s a good idea to always see what’s listening for data. This can be done with the netstat or ss commands with the options -tunap.

Conclusion

There’s a lot more to networking than this. Hopefully, this will get you started on the basics of networking.

| Navigation | ||

|---|---|---|

| < Ch 2 | Home | Ch 4 > |